One of the major contributions which yoga philosophy offers us is the realization that we are not our minds. This realization gives us the freedom to choose which thoughts we act on, talk about and so forth. Yet, the mind is real, and understanding its nature is a vital part of yoga practice.

What is the Mind?

In Bhagavad-gita, Krishna describes the mind as part of the material energy of the Absolute Truth:

bhumir apo ‘nalo vayuh kham mano buddhir eva cha

ahankara itiyam me bhinna prakritir ashtadha

Earth, water, fire, air, ether, mind, intelligence and false ego—all together these eight constitute My separated material energies.

The three items in bold above are defined as:

- Mind — The faculty responsible for selecting between options which can be accepted or rejected.

- Intelligence — The faculty which discerns things from one another, and offers the above options.

- False ego — The sense of self when identified with the mind and body.

Although the first item is called the mind, the word mind also refers to all three of these elements as a whole. This is because the first element is the easiest of the three to manage. By controlling what we accept and reject, we can discern more clearly, and learn to identify as the soul.

We have to accept and reject things constantly in life — everything from meals, to partnerships and books all have effects on our mind. By choosing from spiritual options, and those in the mode of goodness, our intelligence is strengthened, and we gradually disidentify with the body and mind.

What Does the Mind Do?

Mental processes broadly include formation of memories, thinking, feeling and willing. These four processes take place across three stages described in yoga philosophy: dharana, anubhuti and yukti. Here’s an outline of these stages:

- Dharana (Memory Formation) — The mind forms mental impressions of sights, sounds, smells, tastes and tactile sensations. These impressions are preserved as memory.

- Anubhuti (Thinking) — The stored impressions are manipulated in the mind according to the soul’s desires. This process is where both conscious and unconscious thought occurs.

- Yukti (Feeling and Willing) — When we evaluate these thoughts as good or bad, our false ego is reinforced. These feelings develop into decision-making, planning or willing.

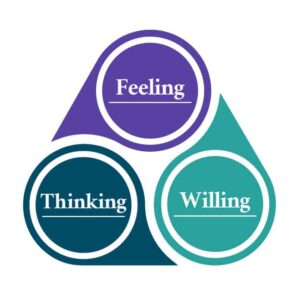

Out of these four processes, thinking, feeling and willing are perceivable, whereas the process of memory formation is subliminal. Because of this, when it comes to the mind, yoga philosophy focuses on thinking, feeling and willing. Picture these three processes as an isosceles triangle:

What Moves the Mind?

Our thoughts and decisions lead to countless behaviors, but what drives them in the first place? Taittariya Upanishad 2.7 explains that we are motivated by the feeling of happiness:

raso vai sah

rasam hy evayam labdhvanandi bhavati

ko hy evanyat kah pranyat

yad esha akasa anando na syat

esha hy evanandayati

The Absolute Truth is the reservoir of pleasure for everyone (rasa). The soul becomes blissful by attaining that rasa. Who would work with the body and sensory powers if this blissful form did not exist? The Absolute Truth gives bliss to all.

This is also confirmed in the Vedanta-sutra in the words ananda-mayo ‘bhyasat, meaning the nature of the soul is to seek pleasure. Yoga is concerned with how we seek pleasure above all other details of the mind. Yoga philosophers describe four lower levels of pleasure seeking:

- Anna-maya — Seeking pleasure through basic sustenance, especially food.

- Prana-maya — Seeking pleasure through experiencing a safe and healthy life.

- Mano-maya — Seeking pleasure through discovery of one’s mental capabilities.

- Vijnana-maya — Seeking pleasure through conclusive understanding of reality.

At first, we’re concerned only with our own happiness. We then recognize others as beings with their own rights instead of as means to an end. The pinnacle of spiritual growth is then to see others as equal shareholders in a relationship to the Absolute Truth, our common source.

This spiritual vision occurs when the innate bliss of the soul, or ananda-maya, is revived through yoga practice. In that stage we still seek pleasure, but now, we seek it for the Absolute, or God. The soul is by nature a secondary enjoyer. We experience bliss in connection with the Absolute.

Yoga means to connect. By realizing the bliss of this connection in our own lives, we’ll see the same potential for happiness in others. This is confirmed in Bhagavad-gita 6.32:

O Arjuna, the perfect yogi, by comparison to his or her self, sees the true equality of all beings, in both their happiness and their distress.

The Mind is a Friend and an Enemy

According to Bhagavad-gita 6.5, the mind is the friend of the conditioned soul, and the enemy as well. The deciding factor as to which one our mind will be in a given moment is identified in the Amrita Bindu Upanishad (2) as follows:

mana eva manushyanam karanam bandha-mokshayoh

bandhaya vishayasango muktyai nirvishayam manah

For humans, mind is the cause of bondage and mind is the cause of liberation. Mind absorbed in sense objects is the cause of bondage, and mind detached from the sense objects is the cause of liberation.

As mentioned, the soul is a secondary enjoyer. Attachment to sense objects occurs when we seek to enjoy the energies of the Absolute Truth without first offering them back to the source. The result is unhappiness in the following three ways:

- We want something, but we don’t get it.

- We get something but it’s not as nice as we had hoped it would be.

- We get something, and it was as good or better than we had hoped, but we lose it.

In order to detach our mind from sense objects then, we adopt the path of bhakti-yoga. Whatever that thing is which you love most produces a unique happiness within you. The process of bhakti-yoga involves offering that happiness to the Absolute Truth, or God.

It may appear that bhakti-yogis are attached to sense objects because they engage them in so many ways. But they are actually detached like a bank teller who counts millions of dollars without claiming ownership of those monies. The teller’s needs are provided for by the bank.

Making Friends with the Mind

Illustrating proper detachment of the mind is very important. Simply giving up an action or relationship due to difficulty is not helpful in making a friend of the mind. Instead, it reinforces the mode of passion’s grip on us. Here’s an example to clearly understand proper detachment:

Pretty much everyone’s bathroom has a toilet brush. Attachment to the toilet brush, as absurd as that may sound, would be, for instance, taking it out of the bathroom, and using it to scrub pots and pans. On the other hand, vowing to never use the toilet brush is also not advisable.

Yoga involves appropriate renunciation, or yukta-vairagya, as described in the masterpiece of devotional yoga, Bhakti-rasamrita-sindhu 1.2.255:

anasaktasya vishayan yatharham upayunjatah

nirbandhah krishna-sambandhe yuktam vairagyam uchyate

When one is not attached to anything but at the same time accepts everything in relation to Krishna, one is rightly situated above possessiveness. On the other hand, one who rejects everything without knowledge of its relationship to Krishna is not as complete in renunciation.